The impacts of network competence, knowledge sharing on service innovation performance: Moderating role of relationship quality

Zhaoquan Jian 1, Chen Wang 2

School of Business Administration, South China University of Technology (China)

Received November

2012

Accepted February 2013

Jian, Z., & Wang, C, (2013). The impacts of network competence, knowledge sharing on service innovation performance: Moderating role of relationship quality. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 6(1), 25-49. http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/jiem.659

---------------------

Abstract:

Purpose: To examine how network competence, knowledge sharing and relationship quality affect service innovation performance

Design/methodology/approach: Empirical research.

Findings: 1) Both enterprise’s network competence and knowledge sharing have distinct positive impact on SIP; (2) Knowledge sharing partially mediates the effect of network competence on SIP. (3) Relationship quality positively moderates the effect of network competence on knowledge sharing, and the effect of knowledge sharing on SIP. (4) Relationship quality does not positively moderate the effect of network competence on SIP.

Originality/value: This study has enriched current understanding of the relationship among network competence, knowledge sharing, relationship quality and service innovation performance.

Keywords: Service Innovation Performance (SIP), Network Competence (NC), Relationship Quality (RQ), Knowledge Sharing (KS).

---------------------

1. Introduction

In the 21st century, the rapid development of global services and the contemporary service-oriented economy has become an irresistible trend of the times; the “service economy” and the era of innovation-based “knowledge economy” has set in; the creation, spread and application of knowledge has become the main driving force to promote the progress of the times. The scale, complexity and interdependence of today’s service systems have been driven to an unprecedented level, due to globalization, demographic changes and technology developments. The rising significance of service and the accelerated rate of change mean that service innovation (SI) is now a major challenge to practitioners in business and government as well as to academics in education and research. A better understanding of service systems is required.

Nowadays, SI represents an interesting area of investigation (Maglio & Spohrer, 2008). Investigating in greater detail of the antecedents of New Service Development (NSD) and Service Innovation Performance (SIP) is a research orientation that deserves attention (Menor, Tatikonda & Sampson, 2002). There are all kinds of antecedents of innovation success, such as culture, strategy, characteristics, people, structure, resources, networking (Jong, Dolfsma, Bruins & Meijaard, 2002). Despite the growing body of service-related scholarly research, the literature from marketing (Hauser, Gerard, & Abbie, 2006), operations (Menor et al., 2002), management (Bowen & Ford, 2002), and innovation (Drejer, 2004) continues to call for research to improve our comprehensive understanding of SI.

Most previous studies focus on manufactory industry, with little attention paid to service industry. Even in operation management, most of the studies focus on tangible “goods”, which is different from services with particular characteristics (heterogeneity, inseparability, perishability) (Jaw, Lo & Lin, 2010). Furthermore, previous empirical investigations of innovation are based on narrow conceptual frameworks that may not fully capture the complexities of service innovation (Baker & James, 2007). Empirical findings in the innovation literature are limited and inconclusive regarding SI antecedents.

Scholars used different theoretical perspectives, such as the Resource-Based View and Transaction Cost theory to derive theoretical rationales for strategic alliance for service innovation. Today, social network perspectives dominate research on interfirm relationships (e.g. Lam, 2003; Perks & Jeffery, 2006). The network approach differs from traditional views in several aspects. Instead of being viewed as a matching game between firms endowed with resources or aimed at minimizing transaction costs, network approach view strategic alliances as a formal agreement between partners to invest in a sustained basis relationship (Chen & Chen, 2002). Hence, strategic alliances are solutions to long-term needs, rather than temporary fixes (Chen & Chen, 2002). There is a need to empirically explore service innovation from the angle of network cooperation, and to explain the detailed driving mechanism of SIP from the angle of multiple resources, such as network capacity, relationship quality, knowledge sharing, etc.

This paper aims to explore in depth the interacting influence of network competence, relationship quality, and knowledge sharing on SIP. We take up samples in service industries to empirically test the model and hypotheses through a questionnaire survey taken by 243 key coordinators or high-level managers. Statistic tools such as SPSS17.0 and AMOS7.0 are used to analyze models and test hypothesizes. These results will enrich current understanding of the mechanism that how network competence, knowledge sharing and relationship quality affect SIP, contribute to the theory of service science and RBV and provide some managerial implication for company to achieve high SIP.

2. Theory foundation and research hypotheses

2.1. Service innovation (SI) and Service innovation performance (SIP)

The initial view of service innovation is attributed to Schumpeter (1934). Later, the notion came to be regarded as the set of innovations in service processes (i.e., service-logic innovation1) for an organization’s existing service products. Moreover, service innovation is regarded as the development of service products which are new to the supplier (Johne & Storey, 1998); an offering not previously available to a firm’s customers resulting from additions to or changes in the service concept (Menor et al., 2002); encompassing ideas, practices or objects which are new to the organization and to the relevant environment, that is to say to the reference groups of that innovator (Van der Aa & Elfring, 2002). Build on the existing literature, we summarize SI as enterprises’ intangible activities formed in the process of service, using a variety of innovative ways to meet customer needs and maintain competitive advantage.

Fitzsimmons (1991) suggested that service innovation is to include two aspects: (1) a broad service innovation covers any innovation activity with service alike attributes that can occur in any part of the economy: manufacturing, agriculture, services or even informal parts of the economy; (2) the narrow service innovation limits to the innovative behavior within the service industry. Thus Den Hertog (2000) took quite a different direction to much standard innovation theorizing, and identified four “dimensions” of service innovation-the service concept, the client interface, the service delivery system and technological options. Storey and Kelly (2001) measured SIP from individual project-level and programmed-level. Herbjorn and Per. (2007) divided SIP into short-term, long-term and indirect performance, according to different strategic objectives of enterprise innovation. Based on previous study, the specific items needed to measure SIP in the current study will be discussed in the process of questionnaire design.

2.2. Influence of network competence on SIP

The concept of network competencies and capabilities is derived (at least in part) from the Resource Based View (RBV) of the firm, a major pillar in the strategic management literature (Barney, 1991). Enterprise resources or competencies are generally defined as all the assets, capabilities, processes and knowledge that reside in the enterprise (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993; Peteraf, 1993). According to Barney and Arikan (2001), the resource-based view of competitive advantage operates on the assumptions that firms are heterogeneous in terms of their control of important strategic resources, and that resources are not perfectly mobile between firms.

Network competence of enterprise is defined as the ability to improve the comprehensive network status and handle specific network relationship. While some focused on enterprise's network position and network setting (Hagedoorn, Nadine & van Hans, 2006), the management and usage of the external network relationships (Ritter, 1999), and both of the two aspects (Ritter, 1999; Ritter & Gemunden, 2004). Arguably, an organization's performance is therefore largely dependent on those with whom it interacts. We argue that the ability of a firm to develop and manage relations with key suppliers, customers and other organisations and to deal effectively with the interactions among these relations is a core competence of a firm - one that has a direct bearing on a firm’s competitive strength and performance, which is referred to network competence.

The innovation benefits of networking identified by the literature include: obtaining access to new markets and technologies (Grandori & Soda, 1995); speeding products to market (Almeida & Kogut, 1999); pooling complementary skills (Eisenhardt & Schoonhoven, 1996); and, acting as a key vehicle for obtaining access to external knowledge (Powell, Koput, & Smith-Doerr, 1996; Cooke, 1996). The evidence from the literature review also illustrates that those firms which do not cooperate and which do not formally or informally exchange knowledge limit their knowledge base on a long-term basis and ultimately reduce their ability to enter into exchange relationships. Previous research had made some achievements on the relationship between network competence and SIP. Moller and Halinen (1999) proposed a network management framework and showed that unique and dynamic networks and network management can improve SIP. Through an empirical research, Ritter and Gemunden (2004) found that network competence had a strong positive impact on the extent of interorganizational technological collaborations and on a firm’s product and process innovation success. Based on previous studies, we propose:

H1: Network competence is positively related to SIP.

2.3. Influence of network competence on knowledge sharing

Knowledge management has become a key factor in the

success

of modern enterprises, with knowledge sharing being a core element. To

stay in

business, companies must take risks and innovate, that is to develop

new

products and services at a high speed and on an efficient scale.

Knowledge

sharing between individuals can increase the exchange of different

knowledge

and enhance organizational capacity, which is more important than

personal

innovation ability (Cohen & Levinthal, 1990). Subsequently,

knowledge

sharing, exchange and assistance among individuals contribute to the

organization's competitive advantage and product's success (Boland

&

Tenkasi, 1995).

Knowledge management has become a key factor in the

success of modern enterprises, with knowledge sharing being a core

element. To stay in business, companies must take risks and innovate,

that is to develop new products and services at a high speed and on an

efficient scale. Knowledge sharing between individuals can increase the

exchange of different knowledge and enhance organizational capacity,

which is more important than personal innovation ability (Cohen &

Levinthal, 1990). Subsequently, knowledge sharing, exchange and

assistance among individuals contribute to the organization's

competitive advantage and product's success (Boland & Tenkasi,

1995).

Therefore, the knowledge, transfer and links that exist among individuals have changed the original economic and competitive value. On the one hand, companies increasingly rely on inputs from others', and the consequence of specialization (increasingly companies choose a business model to specialize in one area, where they develop strong brand names and (patented) technology to grow toward an efficient scale of production) is to innovate (discover new combinations). On the other, because of their specialized advantages, the companies have also become attractive partners for others. This "mutual attraction" has resulted in an innovation trend called "open innovation", in which companies develop new products, markets, or services collaboratively by using each others' know-how, brands, licenses, technology, or market channels.

Nahapiet and Ghoshal (1998) have successfully applied the theory of social embeddedness to the field of strategic management, especially in the interpretation of the capital generation mechanism of internal intellectual knowledge and obtained organizational competitive advantage from "communities of personal interaction" or a central element of knowledge sharing within alliances (Kale & Singh, 2007). They provided a means for regularly and systematically sharing knowledge of alliance management that has already been articulated or codified by the firm. This management knowledge from the outside firms can be an important stimulus for change and organizational improvement. In the light of theory and research methods, this study on the internal transfer and transformation of tacit knowledge, and the cooperative relations unit within the organization has confirmed that network competence does have an important impact on knowledge sharing within organizations. Based on this, the paper raises the following hypothesis:

H2: Network competence is positively related to knowledge sharing.

2.4. Mediating effects of knowledge sharing

Recent research attempts to understand alliance activities from knowledge-based perspective and posits that the sharing of knowledge become central to develop new processes, products, or services in alliance (Gulati, 1998; Hoang & Rothaermel, 2005). Inter-organizational learning is critical to competitive success, noting that organizations often learn by collaborating with other organizations. In a strategic alliance, knowledge sharing can be viewed from the following perspectives. First, firms learn with an alliance partner when the partners jointly enter a new business area and develop new capabilities. Secondly, firms acquire knowledge from alliance partners by gaining access to the skills and competencies the partners bring to the alliance (Baum, Calabrese & Silverman, 2000; Kogut, 1988).

Contingency theory has been used in many contexts, particularly in the field of strategic actions and organizational structure. It examines the effects of related variables (e.g., strategy and business model) on firm performance (Zott & Amit, 2008). We delineate two fundamental strands of contingency theory: the “fit-as-mediation” view and the “fit-as-moderation” view (Drazin & Van de Ven, 1985) The fit-as-mediation view posits that managers choose or adopt organizational structures, processes, and strategies that reflect the particular circumstances of their organizations (Galbraith, 1973). We seek to enrich the debate on the relationship between strategy and SIP. According to the fit-as-mediation view, when faced with keen competition, one of an organization’s predominant responses is to aggressively pursue innovation through interorganizational collaboration. However, we focus in this study on the salient aspects of a firm’s knowledge sharing that account for the effect of network competence on SIP.

Managing knowledge to foster innovation is critical for increasing the development of new products and services (McAdam, 2000). Innovation often results from the combination of existing pieces of knowledge (Fleming, et.al., 2007). Knowledge sharing, therefore, provides informal patterns of interactions for the transformation, recombination, and distribution of knowledge from different places. Knowledge sharing among alliance partners enables a firm to exploit useful knowledge to invest in alliance activities. Studies suggest that a firm's alliance partners are the most important source of new ideas and information that result in performance -enhancing technology and innovations. (Dyer & Singh, 1998; Powell et al., 1996). In this context, alliances provide opportunities to create redeployable knowledge (or private benefits), such as technical knowledge or market knowledge. Thus, alliance partners can generate rents by developing superior inter-firm knowledge sharing routines. The argument that inter-firm collaboration enhances innovation practices has gained wide acceptance among practitioners and researchers. It implies that the amount and variety of knowledge needs to be shared and integrated between firms. Thus, we propose that well-developed mechanism of knowledge sharing can enhance innovation practices and act as a mediator between network competence and service innovation performance. Following contingency theory, we suggest the following hypothesis:

H3: Knowledge sharing mediates the influence of network competence on SIP.

2.5. Moderating effects of relationship quality

Structural contingency theory emphasizes both external and internal fit (Peteraf, 1993). Thus, the second strand of contingency theory we consider here is the fit-as-moderation view (Venkatraman, 1989). This view proposes that a firm’s performance is attributable to a match between its strategic behaviors and the internal and external environment conditions. In this view, firm performance is the dependent variable, network competence is the predictor variable, and relationship quality (i.e., external environment condition) is the contextual variable.

“Relationship quality” was firstly proposed and defined by Crosby and Cowles (1990), who defined relationship quality as the overall evaluation of the strength of buyer-seller relationship, based on the past successful or failed experience. Anderson and Gerbing (1988) proposed that good relationship quality means the customers trust on the service staff and have confidence in the future performance, due to their consistent satisfaction with its past performance. It’s an emerging research to explore the relationship between network competence, relationship quality and SIP. Dion, Easterling and Miler (1995) considered that trust relationship can directly affect corporate performance. Leuthesser (1997) investigated on a variety of manufacturing companies and found that relationship quality has a significant positive impact on sales and market share. Based on the previous study and our interviews, it’s an integrated and realistic way to understand the relationship of the intangible resources (relationship, competence, knowledge) with SIP.

Anderson and Gerbing (1988) considered that when knowledge or resources investment was used as commitment to determine and sustain the relationship, both sides will be more willing to share knowledge, information and technology, which will eventually lead to a greater improvement of SIP. Ritter and Gemunden (2004) suggested that with the development of the network, only when managing network relationships, can the company promote information sharing between partners, learn from each other better and have complementary advantages to improve effectiveness and efficiency.

We propose that SIP is attributable to a match among network competency and relationship quality. The ability to competitively facilitate SIP from network competency is contingent upon the level of relationship quality. We hypothesize that when a firm participates in collaborative projects and activities to acquire critical knowledge/information resources and technological capabilities, to meet customers’ changing needs, or to increase its competitive advantage in the market, relationship quality has moderating effects on the ability of that firm to achieve SIP through network competency. We suppose that the better the relationship quality is, the greater knowledge sharing and SIP is affected by network competence, and the greater SIP is affected by the knowledge sharing. According to contingency theory, relationship quality moderates the effects of network competency on SIP. Therefore, the following hypotheses are offered for testing:

H4: Relationship quality positively moderates the influence of knowledge sharing on SIP.

H5: Relationship quality positively moderates the influence of network competence on knowledge sharing.

H6: Relationship quality positively moderates the influence of network competence on SIP.

3. Method

3.1. Research framework

In this chapter, a comprehensive research model is developed based on a series of literature review. Based on the research framework, the hypotheses are developed to describe and verify the relationship among network capabilities, knowledge sharing, service innovation performance and relationship quality. The research framework is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1 The research model

3.2. Variable Definitions and Measurement

To test the theoretical model and the associated hypotheses, we designed a survey questionnaire on the basis of a comprehensive literature review to specify a set of items that ensured content validity. The self-administered questionnaire was part of a wider examination of network competency, knowledge sharing, SIP and relationship quality. Following the suggestions of Churchill (1979), we adapted, modified, and extended existing scales. Because the study was conducted in China, the survey instrument was in Chinese. Using the parallel-translation method, one person translated the items into Chinese, and then another person translated the Chinese back into English. The two translators then jointly reconciled all differences in wording. The suitability of the Chinese version of the questionnaire was tested in interviews with seven managers from the financial and information service industries (marketing managers, new product managers, product managers, service delivery managers, vice presidents, and market research managers). Then we distributed and collected the questionnaires. All constructs were measured with scales of multiple closed-ended items; responses were based on 5-point Likert scales ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. In particular, we asked managers for their opinions on what service innovation performance their firm had implemented and how they had done so, regardless of their success or failure. We also measured the level of implementation of innovation performance. The higher the score, the more service innovation was implemented in a firm.

This research used self-reported questionnaires to measure network competence, knowledge sharing, service innovation performance and relationship quality. Barriera, Viruet, Sobeih, Daraiseh, and Salem (2006) suggest that self-administrated questionnaires could offer advantages to respondents: (1) Questionnaires are familiar to most people and generally do not make people apprehensive; (2) Questionnaires are very cost effective when studies involving large sample sizes and large geographical areas ; and (3) Any loss of validity is compensated by a larger study size and greater statistical power.

The scale measuring network competence is based on questionnaire of Ritter and Gemunden (2004), which is made up of 11 items, including task implementation and qualification. The measurement scale of relationship quality is mainly according to Hewett, Money and Sharma (2002), Garbarino and Johnson (1999), Roberts, Varki and Brodie (2003), which is made up of 4 items. Knowledge sharing is in the light of studies of Davenport and Prusak (1998), Gupta and Govindarajan (2000), Bock, Zmud and Kim (2005), consisting of 6 items, including knowledge transfer and knowledge receiving . SIP makes reference to the studies of Fizgerald, Johnston, Silvestro, Brignall, and Voss (1991), Storey and Kelly (2001), consisted of 6 indexes such as return on investment, market share et al. We controlled for firm age, size, and capital in our model, as these variables reflect a firm’s resources and market power to exploit existing competencies, build new ones, and develop innovations. We do not propose hypotheses related to these variables here because we are not attempting to develop theory related to their effects.

3.3. Research Samples

This study analyzes data at the firm level. Both the sample and the variables used in this analysis come from the Pearl River Delta of China firms’ survey. The sample is representative of the population of high-tech firms of the Pearl River Delta, because the sampling frame was generated by a random sampling process. The sample includes six high-tech industries (computer hardware, software, precision machinery, biotechnology, optoelectronics and communication equipment). From July, 2010 to January, 2011, we had sent out 485 questionnaires by mail or door to door interview, with 292 returned, with the response rate of 60.2%, and the effective response rate of 50.1%.

Structure of the sample firms is sufficiently diverse and heterogeneous: (1) industry categories: 26.5% in professional, scientific and technical industries, 21.9% in the finance and insurance industry, 14.0% in wholesale and retail, 13.3% in the culture, sports and leisure industry, 6.2% in the optoelectronics industry, 18.1% in logistics, transportation and warehousing services; (2) established time: less than 3 years accounted for 9.5%, 4 to 6 years accounted for 12.8%, 7 to 9 years accounted for 15.2%, 10 to 20 years accounted for 27.6%, 20 to 30 years accounted for 15.2 , 30 to 45 years accounted for 6.6%, more than 50 years accounted for 13.1%; (3) capital sum: less than 10 million Yuan (RMB) accounted for 36.2%, 10 million to 50 million Yuan accounted for 13.6%, 50 million to 100 million Yuan accounted for 7.4%, 100 million to 500 million Yuan accounted for 9.1%, 500 million to 1 billion Yuan accounted for10.7%, more than 1 billion Yuan accounted for 23.0%; (4) number of employees: 33.3% have less than 100 employees, 11.1% have 101 to 200 employees, 15.2% have 201 to 500 employees, 9.5% have 501 to 1000 employees, and 30.9% have more than 1000 employees.

3.4. Reliability and validity of the samples

The scale was developed from prior research and interviews with practitioners. All constructs were measured using a five-point Likert scale to assess the degree to which the respondent agreed or disagreed with each items (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree). Factor loadings, Composite reliability (CR), and Cronbach’s alpha are indicative level of measurement reliability. Composite reliability (CR) value above 0.5 indicates adequate reliability (Fornell & Larcker, 1981), the least value of CR in the survey exceeds 0.83(Table 1), which suggests an acceptable level. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha values of each constructs (Table 1) exceed the suggested level of 0.7, showing internal consistency of each construct (Nunnally, 1978).

|

|

Mean |

S.E |

Composite Reliability |

Cronbach’s Alpha |

Average Variance Extracted |

|

Network Competence |

3.79 |

0.48 |

0.85 |

0.85 |

0.53 |

|

Relationship Quality |

3.74 |

0.48 |

0.83 |

0.82 |

0.54 |

|

Knowledge Sharing |

3.55 |

0.5 |

0.89 |

0.88 |

0.54 |

|

Service Innovation Performance |

3.76 |

0.6 |

0.86 |

0.86 |

0.51 |

Table 1. Means, S.E, CR, Cronbach’s Alpha , AVE

On the validity, the items in the questionnaires of this research are all from the literature that have been published, and we also did some modification and improved the expression according to some experts and pre-test to the scholars and entrepreneurs in the related fields. We also assessed the factorial validity through confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). A construct with either loadings of indicators above 0.5, or a significant t-value above 2.0, or both, is considered to have convergent validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Our model satisfies both requirements, the constructs in the current study demonstrate convergent validity. We assessed convergent validity using the average variance extracted (AVE), or the ratio of construct variance to total variance among indicators. The AVE values for the constructs all exceeded 0.50, confirming that all measures demonstrated satisfactory convergent validity. The AVE can also be used to evaluate discriminant validity. We examined discriminant validity with a correlation matrix. The values of the square root of the AVE for the measures in the diagonal were all greater than the correlations among the measures off the diagonal. Hence, discriminant validity was satisfactory. In Table 2, we present the basic descriptive statistics and correlations of the measures.

|

|

Means |

S.D. |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

|

1.Task qualification |

3.71 |

0.53 |

1.00 |

||||||

|

2.Task implementation |

3.87 |

0.60 |

0.45** |

1.00 |

|||||

|

3.Satisfaction |

3.62 |

0.55 |

0.31** |

0.29** |

1.00 |

||||

|

4.Trust |

3.59 |

0.60 |

0.26** |

0.27** |

0.52** |

1.00 |

|||

|

5.Commitment |

3.68 |

0.59 |

0.31** |

0.23** |

0.24** |

0.45** |

1.00 |

||

|

6.Knowledge sharing |

3.55 |

0.50 |

0.44** |

0.43** |

0.33** |

0.37** |

0.27** |

1.00 |

|

|

7.SIP |

3.76 |

0.60 |

0.55** |

0.56** |

0.33** |

0.33** |

0.36** |

0.67** |

1.00 |

Table 2. Means, standard deviations, and correlations

4. Results and conclusions

With the literature review and case interview, this paper constructs a theoretical model and studies the relationships among network capacity, knowledge sharing, service innovation performance (SIP) and relationship quality, selecting 102 high-tech firms in Pearl River Delta as the empirical research sample. Statistical analyses present some interesting findings as follows: (1) Both enterprise’s network competence and knowledge sharing has a distinct positive impact on SIP, and knowledge sharing partially mediate the effect of network competence on SIP. (2) Relationship quality has a positive moderating effect on the relations between network competence and knowledge sharing, and between knowledge sharing and SIP. (3) The hypothesis that relationship quality positively moderates the relation between network competence and SIP is rejected. These results enrich current understanding of the relationships among network competence, knowledge sharing, relationship quality and service innovation performance.

We argue that incorporating network competency into our analysis leads to a more comprehensive view of the strategic behavior of firms. Traditional strategy research views firms as seeking to build resources and possess market positions that lead to sustainable competitive advantage. However, according to RBV and contingency theory, firms are more likely to connect to one another in a competitive environment to facilitate service innovation performance. Using data collected from service firms that have implemented service innovation, this study provides evidence to suggest that the moderating effects of relationship quality potentially reinforce the contingency theory, which requires a more sophisticated managerial approach to service innovation across industries.

4.1. Results for the direct effects

A bootstrapping technique was used to determine the significance of the structural paths. The path coefficients for the research constructs are expressed in a standardized form. The predictive power of the research model was assessed by examining the explained variance (R2) for the endogenous constructs. For most firms, the positive relationship between network competency and SIP was significant (b = 0.54, t =10.07, p <0.001), the positive relationship between network competence and knowledge sharing was significant (b = 0.39, t = 6.50, p < 0.001). Thus, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were supported. Together, the significant hypotheses explained a substantial amount of the variance in the endogenous constructs.

Through model validation we find that the path coefficient between network competence and the service innovation performance was positive and statistically significant positive (b = 0.54, t =10.07, p <0.001), this result indicates that network competency plays a positive role in service innovation performance. In this paper, the main measurements of service innovation performance include development costs of new service product, returns on investment, market share and customer satisfaction. Innovative behavior services such as new product development demand a lot of technology, services and market information, also have to bear the enormous market risk at the same time. This collaboration-based view of organizing service innovation practices prior work on service process innovation, which had focused largely on technical capability and risk reduction. Therefore, enterprises need to integrate internal and external networks of relationships and resources to reduce the risk of service innovation and to improve output efficiency of service innovation.

The fully standardized effect of service innovation performance and knowledge sharing is 0.39, and it goes through the significance test under the 99.9% confidence level, indicating there is a significant positive correlation between knowledge sharing and service innovation performance, thereby supporting hypothesis H2. Research on knowledge sharing’s impact on the performance of technological innovation has been relatively mature, and enjoys a high degree of consistency in findings; while after analyzing sufficient samples and doing standard empirical studies, this study on the other hand strongly supports the significant impact of knowledge sharing on service innovation performance, which is rare in the current research. Knowledge sharing plays an important part when enterprise is constantly seeking to grow. In the light of the cooperation objectives, the compromise of views, the communication and the information sharing will greatly improve the sensitivity of the market; increase the fitness degree of cooperative behaviors in service innovation; and make the service innovative output meet market demand through the improvement of innovation efficiency.

4.2. Results for mediating effects

To assess the extent of mediation in the model, we followed Andrews, Netemeyer, Burton, Moberg and Christainsen (2004), who indicated that four specific criteria must be met: (1) The independent variable should significantly influence the mediator variable; (2) the mediator should significantly influence the dependent variable; (3) the independent variable should significantly influence the dependent variable; and (4) after the mediator variable is controlled, the impact of the independent variable on the dependent variable should no longer be significant (for full mediation) or should be reduced in strength (for partial mediation). In this study, the independent variable was network competency, and the proposed mediating variables was knowledge sharing. The dependent variable was SIP. As shown in Table3, Model 1 did not include the mediator of knowledge sharing. The fourth condition held if the effects of network competence on SIP became insignificant or less significant after the mediator of knowledge sharing was included. Model 2 results showed that entering the mediator of knowledge sharing indeed decreased the impact of network competency from b=0.54 to 0.40. In particular, the impact of network competency on SIP was diminished (but still significant), indicating partial mediation. Correspondingly, knowledge sharing partially mediated the relationship between network competency and SIP; thus, Hypothesis 3 was supported.

The present results support the idea that network competency influences service innovation performance in part because it facilitates knowledge sharing. For most firms, the relationship between network competency and service innovation performance is partially mediated by knowledge sharing. This suggests that network competency, in addition to being positively associated with knowledge sharing, has a direct and positive association with service innovation performance. These findings indicate that network competency yields service innovation performance through knowledge sharing.

In corporate innovation between service-oriented business and external partners, the interactive process of knowledge and information transfer and sharing is essential. Knowledge sharing can improve the efficiency and benefit of cooperation, enhance mutual trust, so that both sides receive useful complementary information with lower cost and thus raising the success rate and profitability of innovation projects, therefore, an emphasis on cooperation in knowledge sharing can achieve a higher service innovation performance rate. Overall, mediation by knowledge sharing lends empirical support to the theoretical perspective that service innovation relies on the ability of the organization to apply knowledge sharing to service innovation.

|

Model |

Independent variables |

Beta |

t |

R2 |

F |

△R2 |

|

1 |

Constant |

0.06 |

0.3 |

101.41*** |

||

|

Network competence1 |

0.54 |

10.07 *** |

||||

|

2 |

Constant |

0.07 |

0.42 |

87.62*** |

0.126 |

|

|

Network competence |

0.4 |

7.43 *** |

||||

|

Knowledge sharing |

0.38 |

7.23 *** |

||||

|

3 |

Constant |

-0.2 |

0.45 |

38.32 *** |

0.025 |

|

|

Network competence |

0.35 |

6.44 *** |

||||

|

Knowledge sharing |

0.36 |

6.56 *** |

||||

|

Relationship quality |

0.11 |

2.07 * |

||||

|

RQ*NC |

-0.09 |

-1.52 |

||||

|

RQ*KS |

0.14 |

2.41 * |

||||

|

4 |

Constant |

0 |

0.15 |

42.3*** |

0.149 |

|

|

Network competence2 |

0.39 |

6.50*** |

||||

|

5 |

Constant |

-0.62 |

0.2 |

20.05*** |

0.052 |

|

|

Network competence |

0.35 |

5.65*** |

||||

|

Relationship quality |

0.19 |

3.16 ** |

||||

|

RQ*NC |

0.13 |

2.24 * |

Table 3. Regression Results. (In Model 1, 2, 3 knowledge sharing as mediator, relationship quality as moderator, SIP as dependent variable; in Model 4, 5 relationship quality as moderator, knowledge sharing as dependent variable. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001)

4.3. Results for moderating effects

The moderating effects models (see Tables 3) tested the extent to which relationship quality moderated the main effect hypothesized in Hypothesis 1 and 2. We mean-centered network competence, knowledge sharing, SIP and relationship quality before we generated the interaction terms. Then we added the interaction terms from Model 2 to Model 3. As shown in Table 3, Model 3 indicated that the interaction term of RQ × KS had a significant positive moderating effect on the association between knowledge sharing and SIP; Model 6 indicated that the interaction term of RQ × NC had a significant positive moderating effect on the association between network competence and knowledge sharing. Thus, Hypothesis 4 (b = 0.14, p < 0.05) and Hypothesis 6 (b=0.13, p<0.05) were supported, which confirms the moderating role of relationship quality. However, Hypothesis 5 was not supported. It comes out a surprise that the relationship quality’s moderating effect is negative. When the relationship quality is higher, network competence will not influence SIP so much, it imply that relationship and competence are alternative in China, although the moderating effect doesn’t have a statistical significance (b= -0.09, p>0.10)

Figure 2. Moderating effect of RQ on the relation of KS and SIP

Figure 3. Moderating effect of RQ on the relation of NC and KS

As results in regression model (Table 3) show, relationship quality is not so related to SIP as the other two resources (network capacity and knowledge sharing), but it has an indirect and positive moderating effect on SIP by speeding up both the impact of knowledge sharing on SIP and the impact of network competence on knowledge sharing. The direct effect model is not sufficient for explaining how network competency and knowledge sharing lead to service innovation. There is an additive effect of the set of integration mechanisms on building service innovation such that the effect of each integration mechanism depends upon commingling with network competency and knowledge sharing. We found that the association of building relationship between knowledge sharing, network competence and service innovation is contingent on the presence of relationship quality.

Relationship has abundant meaning in China, not only expressed as emotion exchange and interest fulfillment, but also an essential element embedded in knowledge sharing, network cooperation and service innovation success. According to RBV, enterprise with long-term possession of unique resources access to lasting excess profits and competitive advantage. They can lead to competitiveness advantage, as well as to obtain a near monopoly position in its chosen markets (Rumelt, 1994; Prahalad & Hamel, 1990). Our study supports the RBV empirically by explaining the relationship of different resources and their integrated influences on SIP.

5. Conclusion and implication

5.1. Theoretical and practical implications

This paper makes noteworthy contributions to the literature, which tries to systematically examine how firms create and extract value from their networks. Studies of networks tended to focus on structures, relations, and outcomes. Drawing on multiple bodies of related literature, we developed a framework to investigate the relations of knowledge sharing, network competence, relationship quality and service innovation performance.

First, according to Dhanarag and Parkhe’s (2006) suggestion, interfirm relationship studies have progressed at two levels: dyadic and network. Traditional studies of dyadic alliances have often focused on the transactional level, relating partner characteristics to alliance processes. The next stage of theory development must embrace interfirm networks’ player-structure duality by taking into account both the structural inducements and constraints of the network, as well as organizational action that perpetuates the network (Dhanarag & Parkhe, 2006). This study attempts to extend this stream of research. I believe this is a critically important yet underexplored issue in building effective networks.

Second, it develops theory around the idea of network competency and knowledge sharing in service innovation practices; the perspective that service innovation performance can be viewed as a practice of embodying network competency and knowledge sharing is a novel complement to prior research on service innovation. Our study provides empirical evidence of the different effects of the resources on SIP by showing that network resources are important contributors to SIP improvement, although in different ways. What’s more, knowledge sharing shows both direct and mediated effect on SIP, and is apparently the one of the most important factors for SI. Furthermore, our study contributes to the evolving literature on SDL. In particular, it offers empirical support for the suggestion in the current SDL literature that network competence, relationship, knowledge are immaterial and intangible resources, which have different impact on SIP.

Third, the demonstration on moderating effect of relationship quality sheds new light on the contentious role of relationship quality, showing that effect of relationship quality is synergistic and complex. By this way, our study also gives a broader understanding why theory of relationship (Guanxi) and relationship marketing is so important, everlasting and popular in China. Moreover, our studying makes contribution to broader understanding the theory of service supply chain management and open-network service innovation, which s a scientific and unavoidable way to study SI on the angle of network.

This study also has significant implications for managers.

First, we try to open the black box of why companies differ in their ability to operate in networks. Managers have regarded forming alliances as a shortcut to obtaining competitive advantage and resources from other firms. Nevertheless, they neglect the costs or inefficiency that alliances may bring. In this study, we identify firms’ ability to manage alliance networks as “network competence”. The empirical results presented here have shown that a positive and significant link exist between a firm’s network competence and alliance performance. Thus, firms are advised to enhance their network competence. The results suggest that managers should assess network competency for new service innovation development—that is, task implementation and task qualification—in the process of developing SIP. They should identify areas in which their firms may be lacking and develop specific capabilities for improving network competency. Such an assessment is important for facilitating competency and should precede any large-scale service innovation implementation projects. In other words, managers pick one of network capabilities alone may not be sufficient for ensuring a successful outcome unless the two capabilities can be combined effectively.

Second, managers can enhance innovation performance in service development processes by establishing knowledge sharing with partners. The present findings indicate that compatibility of partners is critical to enhancing service innovation. At the same time, firms should work closely to maintain stable and enduring collaborative relationships; frequent learning interactions between managers and salespersons to explore the mutuality of their interests and needs should be encouraged.

Third, we should understand and utilize the moderating mechanism of the relationship quality in the complex model. As most Chinese people pay attention to the relationship (Guanxi) to achieve goals, this study indicates that relationship should also be emphasized by managers if they want to achieve high performance in SI. Especially, our findings highlight the critical role of relationship quality —with which, collaboration and network emerge as the most important innovation trigger to engage outside stakeholders’ resources to improve SIP.

5.2. Limitations and future research

This study has several limitations. First, these preliminary findings must be validated in future longitudinal studies. Moreover, the model is not robust enough to include all possible factors related to service innovation performance; future work should consider factors that might influence knowledge and technology integration strategies for facilitating service innovation in different industries, such as quality management, human resources management, technology management, financial management, and so on. Developing and testing more comprehensive models of service innovation is a potentially fruitful avenue for future research.

Second, because we used the key respondent approach and directed our questionnaire to managers, the results may be subject to single-informant bias. A reasonable argument can be made that managers’ knowledge about service innovation performance may reflect a positive bias. Future research that includes top executives or other senior staffs would help clarify whether the results reported herein generalize beyond managers.

Third, although we controlled for firms’ age, capital, and size, we did not include other potentially influential covariates such as industry maturity and research and development strength (Calantone, 1998). This might limit the evaluation of the relative importance of the network competency and service innovation performance, and it highlighted an avenue for future research.

Fourth, the research has some new findings as well as some questions that need further discussion. First, this study is based on the six high-tech industries are all from Pearl River Delta of China, thus, to generalize and further explore the effects of culture on the SIP mechanism across industries and regions, survey samples can be extended (include more service industries) in order to verify the generalizability. And, it would be interesting to extend and verify our proposed framework in other distinct geo-cultural contexts (e.g., the Yangtze River Delta of China, Bohai Economic Rim).

Despite these limitations, our study highlights the key role of knowledge sharing and relationship quality in enhancing service innovation performance and underscores the central importance of network competency. We propose that firms in different industries with the same network competency but differential effects on relationship quality could achieve service innovation performance of varying effectiveness. Examining the role of network competency in service innovation without isolating and accounting for relationship quality may lead to incomplete understanding or even misleading results. Therefore, we challenge researchers and managers to make a more sophisticated assessment of how and why network competency affects service innovation performance. We believe by delineating the relative effect of network competency and by showing the mediating role of knowledge sharing and moderating roles of relationship quality, this study illuminates in a systematic way how such a goal can be achieved.

Appendix Measurement

instrument

|

Model fit: CMIN/df=2.629;CFI=0.889;AGFI=0.811;RMSEA=0.082 |

|

|

Network competence [NC] |

|

|

To what extent do the following statements represent your organization? |

Std.items |

|

NC1:Our company(coordinators) know very well about the operation of ours |

0.72 |

|

NC2:Our company(coordinators) know very well about the operation of the partners. |

0.79 |

|

NC3:Our company(coordinators) have great experience in communicating with partners. |

0.71 |

|

NC4:Our company(coordinators)s have a keen scent for potential conflict with partners. |

0.70 |

|

NC5:Our company(coordinators) can give constructive proposals when there is a conflict. |

0.73 |

|

Relationship Quality [RQ] |

|

|

To what extent do the following statements represent your organization? |

Std.items |

|

RQ1:Your company is satisfied with products provided by cooperative partners. |

0.66 |

|

RQ2:Your company is greatly satisfied with the cooperative relationship. |

0.81 |

|

RQ3:Your company is greatly satisfied with the date of delivery. |

0.73 |

|

RQ4:Your company is greatly satisfied with the approaches in communication with partners. |

0.74 |

|

Knowledge Sharing [KS] |

|

|

To what extent do the following statements represent your organization? |

Std.items |

|

KS1:Your company is willing to share information related to service with cooperative partners. |

0.64 |

|

KS2:Cooperative partners. are willing to share market information or customers’ needs with your company. |

0.58 |

|

KS3:Cooperative partners are willing to share information related to service with your company. |

0.71 |

|

KS4:Your company share the information of market share and customers’ needs with cooperative partners. |

0.81 |

|

KS5:Your company share technology change information of important product/service with cooperative partners. |

0.87 |

|

KS6:Your company and cooperative partners share strategy or its change mutually. |

0.93 |

|

Service Innovation Performance [SIP] |

|

|

To what extent do the following statements represent your organization? |

Std.items |

|

SIP1:Service innovation in our company has a high rate of return on investment. |

0.77 |

|

SIP2:Service innovation in our company can improve the market share of the company. |

0.76 |

|

SIP3:Service innovation in our company can significantly reduce the cost of the company. |

0.61 |

|

SIP4:Service innovation in our company can improve the customer satisfaction. |

0.68 |

|

SIP5:Service innovation in our company can improve the competitiveness of the company. |

0.76 |

|

SIP6:Service innovation in our company can help company realize the business objectives. |

0.71 |

References

Almeida, P., & Kogut, B. (1999). Localization and Knowledge and the Mobility of Engineers in Regional Networks. Management Science, 45(7), 905-917. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.45.7.905

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. (1993). Strategic Assets and Organizational Rent. Strategic Management Journal, 14(1), 33-46. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140105

Anderson, J.C., & Gerbing, D.W. (1988). Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-step Approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411-423. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

Andrews, J.C., Netemeyer, R.G., Burton, S., Moberg, D.P., & Christainsen, A. (2004). Understanding Adolescent Intentions to Smoke: An Examination of Relationships among Social Influences, Prior Trial Behaviors, and Ant tobacco Campaign Advertising. Journal of Marketing, 68(3), 110-123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.3.110.34767

Baker, W.E., & James, M.S. (2007). Does Market Orientation Facilitate Balanced Innovation Programs? An Organizational Learning Perspective. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 24 (summer), 316-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2007.00254.x

Barney, J.B. (1991). Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99-120. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

Barney, J.B., & Arikan, A. (2001). The Resource-based View: Origins and Implications, The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management. Oxford: Blackwell Business, 124-188.

Barriera-Viruet, H., Sobeih, T.M., Daraiseh, N., & Salem, S. (2006). Questionnaire v.s. Observational and Direct Measurements: a Systematic Review. Theoretical Issues in Ergonomics Science, 7(3), 261-284. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14639220500090661

Baum, J.A.C., Calabrese, T., & Silverman, B.S. (2000). Don't Go It Alone: Alliance Network Composition and Startups' Performance in Canadian Biotechnology. Strategic Management Journal, 21(3), 267-294. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200003)21:3<267::AID-SMJ89>3.0.CO;2-8

Bock, G.W., Zmud, R.W., & Kim, Y.G. (2005). Behavioral Intention Formation in Knowledge Sharing: Examining the Roles of Extrinsic Motivators, Social Psychological Forces, and Organizational Climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87-111.

Boland, R.J., & Tenkasi, R.V. (1995) Perspective Making and Perspective Taking in Communities of Knowing. Organization Science, 6(4), 350-372. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.6.4.350

Bowen, J., & Ford, R.C. (2002). Managing Service Organizations: Does Having a ‘Thing’ Make a Difference? Journal of Management, 28(3), 447-469.

Chen, H., & Chen, T.J. (2002). Asymmetric Strategic Alliances: a Network View. Journal of Business Research, 55(12), 1007-1013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00284-9

Cohen, W.M., & Levinthal, D.A. (1990). Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation. Administrative Sciences Quarterly, 35, 569-596. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2393553

Crosby, L.A., & Cowles, D. (1990). Relationship Quality in Service Selling: An Inter-personal Influence Perspective. Journal of Marketing, 54(7), 54-82.

Davenport, T.H., & Prusak, L. (1998). Working Knowledge: How Organizations Manage What They Know. MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Den Hertog, P. (2000). Knowledge-intensive Business Services as Co-producers of innovation, International Journal of Innovation Management, 4(4), 491-528.

Dhanarag, C., & Parkhe, A. (2006). Orchestrating Innovation Networks. Academy of Management Review, 31(3), 659-669. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2006.21318923

Dion, P., Easterling, D., & Miller, S.J. (1995), What Is Really Necessary in Successful Buyer/Seller Relationships? Industrial Marketing Management, 24, 1-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0019-8501(94)00025-R

Drazin, R., & Van De Ven, A.H. (1985). Alternative Forms of Fit in Contingency Theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(4), 514–539. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2392695

Drejer, I. (2004). Identifying Innovation in Surveys of Services: A Schumpeterian Perspective. Research Policy, 33(3), 551-562. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2003.07.004

Dyer, J.H. & Singh, H. (1998). The Relational View: Cooperative Strategy and Sources of Interorganizational Competitive Advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(4), 660-679.

Eisenhardt, K., & Schoonhoven, C. (1996). Resource-based View of Strategic Alliance Formation: Strategic and Social Effects in Entrepreneurial Firms. Organization Science, 7, 136-150. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.2.136

Fizgerald, L., Johnston, R., Silvestro, R., Brignall, T.J., & Voss, C. (1991). Performance Measurement in Service Business. London: CIMA.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Galbraith, J. (1973). Designing Complex Organizations. Reading. MA: Addison-Wesley.

Garbarino, E., & Johnson, M.S. (1999). The Different Roles of Satisfaction, Trust, and Commitment in Customer Relationships, Journal of Marketing, 63(2), 70-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/1251946

Grandori, A., & Soda, G. (1995). Inter-firm Networks: Antecedents, Mechanisms and Forms. Organization Studies, 16(2), 183. http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/017084069501600201

Gulati, R. (1998). Alliances and networks. Strategic Management Journal, 19(4), 293-317. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199804)19:4<293::AID-SMJ982>3.0.CO;2-M

Gupta, A.K., & Govindarajan, V. (2000). Knowledge Flows within Multinational Corporations. Strategic Management Journal, 21(4), 473-496. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200004)21:4<473::AID-SMJ84>3.0.CO;2-I

Hagedoorn, J., Nadine R., & van Hans, K. (2006). Inter-firm R&D Networks: the Importance of Strategic Network Capabilities for High-tech Partnership Formation. British Journal of Management, 17, 39-53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2005.00474.x

Hauser, J., Gerard, J.T., & Abbie, G. (2006). Research on Innovation and New Products: A Review and Agenda for Marketing Science. Marketing Science, 25(6), 687-717. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mksc.1050.0144

Herbjorn, N., & Per, E.P. (2007). What Can We Learn From Service Innovation and New Service Development Research? TIPVIS-project report.

Hewett, K., Money, R.B., & Sharma, S. (2002), An Exploration of The Moderating Role of Buyer Corporate Culture in Industrial Buyer-seller Relationships. Academy of Marketing Science, 30(3), 229-239.

Hoang, H., & Rothaermel, F.T. (2005). The Effect of General and Partner -specific Alliance Experience on Joint R&D Project Performance. Academy of Management Journal, 48(2), 332-345. http://dx.doi.org/10.5465/AMJ.2005.16928417

Jaw, C., Lo, J.Y., & Lin, Y.H. (2010). The Determinants of New Service Development: Service Characteristics, Market Orientation, and Actualizing Innovation Effort. Technovation, 30(4), 265-277. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.11.003

Johne, A., & Storey, C. (1998). New Service Development: A Review of the Literature and Annotated Bibliography. European Journal of Marketing, 32(3/4), 184-251. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090569810204526

Jong, J.P.J. de, W. Dolfsma, A., Bruins, & Meijaard, J.(2002). Innovation in Service Firms Unraveled: What, How and Why. EIM, Zoetermeer.

Kale, P., & Singh, H. (2007). Building Firm Capabilities Through Learning: the Role of the Alliance Learning Process in Alliance Capability and Firm -level Alliance Success. Strategic Management Journal, 28(10), 981-1000. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.616

Kogut, B. (1988). Joint Ventures: Theoretica and Empirical Perspectives. Strategic Management Journal, 9(4), 319-332. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250090403

Lam, A. (2003). Organizational Learning in Multinationals: R&D Networks of Japanese and US MNEs in the UK. Journal of Management Studies, 40(3), 673-703. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00356

Leuthesser, L. (1997). Supplier Relational Behavior: An Empirical Assessment. Industrial Marketing Management, 26(3), 245-254. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(96)00092-2

Maglio, P. P., & Spohrer, J. (2008). Fundamentals of Service Science. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 36(1), 18-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0058-9

McAdam, R. (2000). Knowledge Management as a Catalyst for Innovation within Organizations: A Qualitative Study. Knowledge and Process Management, 7(4), 233-241. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/1099-1441(200010/12)7:4<233::AID-KPM94>3.0.CO;2-F

Menor, L.J., Tatikonda, M.V., & Sampson, S.E. (2002). New Service Development: Areas for Exploitation and Exploration. Journal of Operation Management, 20(2), 135-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0272-6963(01)00091-2

Möller, K., & Halinen, A. (1999). Business Relationships and Networks: Managerial Challenge of Network Era . Industrial Marketing Management, 28(5), 413-427. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(99)00086-3

Nahapiet, J., & Ghoshal, S., (1998). Social Capital, Intellectual Capital, and the Organizational Advantage. Academy of Management Review 23, 242-266.

Perks, H., & Jeffery, R. (2006). Global Network Configuration for Innovation: a Study of International Fibre Innovation. R&D Management, 36(1), 67-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2005.00416.x

Peteraf, M.A. (1993). The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View. Strategic Management Journal, 14, 179-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250140303

Powell, W.W., Koput, K.W., & Smith-Doerr, L. (1996). Inter-organizational Collaboration and the Locus of Innovation: Networks of Learning in Biotechnology. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(1), 116-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2393988

Ritter, T. (1999). The Networking Company: Antecedents for Coping with Relationships and Networks Effectively. Industrial Marketing Management, 28(5), 467-479. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0019-8501(99)00075-9

Ritter, T., & Gemunden, H.G. (2004). The Impact of a Company’s Business Strategy on its Technological Competence, Network Competence and Innovation Success. Journal of Business Research, 57(5), 548-556. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(02)00320-X

Roberts, K., Varki, S., & Brodie, R. (2003). Measuring the Quality of Relationships in Consumer Services: an Empirical Study. European Journal of Marketing, 37(1/2), 169-196. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/03090560310454037

Storey, C., & Kelly, D. (2001). Measuring the Performance of New Service Development Activities. The Service Industries Journal, 21(2), 71-90. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/714005018

Van der Aa, W., & Elfring, T. (2002). Realizing Innovation in Services, Scandinavian Journal of Management 18(2), 155-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(00)00040-3

Venkatraman, N. (1989). The Concept of Fit in Strategy Research: Toward a Verbal and Statistical Correspondence. Academy of Management Review, 14(3), 423–444.

Walter, A., Auer, M., & Ritter, T. (2006). The Impact of Network Capabilities and Entrepreneurial Orientation on University Spin-off Performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 21(4), 541-567. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.02.005

Walter. A., Auer, M., & Ritter, T. (2003). Innovation Management: Strategies, Implementation, and Profits. NY: Oxford.

Zott, C., & Amit, R. (2008). The Fit between Product Market Strategy and Business Model: Implications for Firm Performance. Strategic Management Journal, 29(1), 1-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.642

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

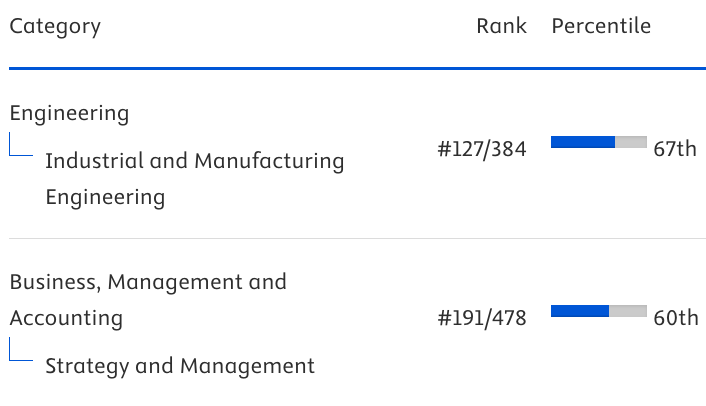

Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 2008-2026

Online ISSN: 2013-0953; Print ISSN: 2013-8423; Online DL: B-28744-2008

Publisher: OmniaScience