Job stress with supervisor’s social support as a determinant of work intrusion on family conflict

Azman Ismail, Fara Farihana Suhaimi, Rizal Abu Bakar, Syed Shah Alam

Received: May 2013

Accepted: November 2013

Ismail, A., Farihana Suhaimi, F., Abu Bakar, R., & Shah Alam, S. (2013). Job stress with supervisor’s social support as a determinant of work intrusion on family conflict. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 6(4), 1188-1209. http://dx.doi.org/10.3926/jiem.858

---------------------

Abstract:

Purpose: The primary objective of this study is to examine the influence of supervisor’s social support in the correlation between job stress and work intrusion on family conflict.

Design/methodology/approach: A survey method was employed to gather survey questionnaires from academic staff in a Malaysian government university in Borneo. Findings: The outcomes of SmartPLS path model showed three major findings: first, supervisor’s social support does act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role ambiguity and work intrusion on family conflict. Second, supervisor’s social support does not act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role conflict and work intrusion on family conflict. Third, supervisor’s social support does not act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role overload and work intrusion on family conflict. In sum, supervisor’s social support does act as a partial moderating variable in the hypothesized model.

Findings: The outcomes of SmartPLS path model showed three major findings: first, supervisor’s social support does act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role ambiguity and work intrusion on family conflict. Second, supervisor’s social support does not act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role conflict and work intrusion on family conflict. Third, supervisor’s social support does not act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role overload and work intrusion on family conflict. In sum, supervisor’s social support does act as a partial moderating variable in the hypothesized model.

Practical implications: The findings of this study can be used as guidelines by management to overcome job stress problems through updating the content and methods of stress management training program, strengthening work groups and group cohesiveness in executing job, improving work-life balance programs to reduce the employee physiological and psychological stresses, revisiting the existing job designs based on the qualifications and expectations of individual employees, and revising compensation and benefits policies and procedures to cover stress-related disorder diseases, and activating internal employee assistance programme in order to help employees and their families with problems arising from both work-related and external resources. If these suggestions are given highly attention this may increase the capability of employees to enhance the performance of institutions of higher learning.

Originality/value: The role of supervisor’s social support in influencing the effect of job stress on family conflict is commonly investigated in Western countries, but it has not been thoroughly studied in the context of this study.

Keywords: job stress, supervisor’s social support, work intrusion on family conflict

---------------------

1. Introduction

Most of the research on work stress have been focused on the stressor-strain nucleus of the traditional stress models and developed them for work context (Poelmans, 2001). Early stage of the research on the development of work-family conflict (WFC) model researcher introduced family as an extra-organizational stressor in their work and stress model Matteson and Ivancevich (1979). Researchers assumed from this model is that some stressors at different levels that cause strain in the individual, moderated by a number of individual differences (Poelmans, 2001). This strain finally create behavioural, cognitive and physiological problems. Based on the demand-control-support model researchers argued that jobs that combine stressful working conditions, such as high workloads, with low levels of control or decision latitude and limited social support are associated with more stress, more health problems and lower job performance (Karasek, 1985; Karasek & Theorell, 1990).

Stress is a situation or an emotion experienced when a someone feels that “demands go beyond the personal and social resources the individual is able to marshal” (Lazarus, 1966). In other words, it is a situational feeling when one thinks one has lost control of events (Dar, Akmal, Naseem & Khan, 2011). In any organization for example, job stress is not uncommon. The incidents of job stress reported by workers have increased steadily in the last decade (Bliese & Britt, 2001; Brouwers, Evers & Welko, 2001; O’Driscoll & Brough, 2003). A recent study found that 33% of stress was caused by factors outside the organization while 67% of stress was caused by internal, company factors. The internal factors included heavy or difficult work load, working long hours, leadership (or lack thereof), and work environment (Bhatti, Shar, Shaikh & Nazar, 2010).

In an organizational context, many scholars like Fu and Shaffer (2001), Major, Klein and Ehrhart (2002), Eby, Casper, Lockwood, Bordeaux and Brinley (2005), Ismail, Mohamed, Sulaiman, Ismail and Mahmood (2010), and Yu-Fei, Ismail, Ahmad and Kuek (2012) view job stress as a multidimensional concept that comprises three salient characteristics: role ambiguity, role conflict and role overload. Firstly, role ambiguity is often viewed as an employee does not have clear information about his or her work objectives, work scope, supervisor’s expectations, and responsibilities of his or her job may lead to higher job-related tension. Secondly, role conflict is usually seen as an employee feels dilemma with his/her job demand; doing things he or she does not want to do, or doing things that is not considered part of his/her job. Being in between these two things requires an individual to make decision and making decision under conflicting demands is frequently stressful. It is seen as an employee is expected to do his/her job that may cause conflict with other job or non-job demands. Finally, role overload is normally referred to as an employee associates with too-heavy work burden which is beyond one’s capability to cope and often results in stress. There are two different types of role overload described by researchers; quantitative and qualitative. Quantitative overload simply refers to having too much work to do, whereas qualitative overload refers to a work that is too difficult for an individual.

A review of recent organizational support literature highlights that the ability of employees to properly handle role ambiguity, role conflict and role overload may decrease the intrusion of work problems in employees’ family affairs and increase their abilities to decrease family conflict (Schiem & Young, 2010; Yildirim & Aycan, 2008). Many scholars like Boles, Howard and Donofrio (2001), Major et al. (2002); Yildirim and Aycan (2008), and Schiem and Young (2010) generally view that work intrusion on family conflict as work obstructs employees’ family affairs and thus may disturb their family wellbeing. It can occur in three major forms: time-based, strain-based and behavior-based. First, time-based conflict occurs when the time demands of one role are incompatible with those of another (e.g., working overtime forces an individual to cancel a family outing). Second, strain-based conflict occurs when tension experienced in one role interferes with participation in another role (e.g., meeting key performance indicators prevents an individual to concentrates on family matters). Third, behavior-based conflict occurs when behavior patterns appropriate to one role are inappropriate in another (e.g., emotional restrictions at work are contrary with the openness expected by family members). In the workplace, individual employees have different capabilities in handling job stress and in controlling the effect of job stress on their family conflict. For example, individuals who have experienced moderate and low stress levels in executing job will be able to manage their physiological and psychological stresses. In this situation, it may decrease their family conflict. Conversely, individuals who have experienced high stress levels in implementing job will not be able to control and manage their physiological and psychological stresses. As a result, it may increase their family conflict (Ismail et al., 2010; Yu-Fei et al., 2012).

Unexpectedly, a further investigation of the workplace stress reveals that the effect of job stress on family conflict is not consistent if supervisor’s social support is present in organizations (Fu & Shaffer, 2001; Goldsen & Scharlach, 2001; Yu-Fei et al., 2012). Supervisor’s Social Support is viewed as involving perceptions that one has access to supervisor who is rendering a helping relationship of varying quality or strength that provide resources such as communication of information, emotional empathy or tangible assistance (Viswesvaran, Sanchez & Fischer, 1999). Additionally, House (2003) views supervisor’s social support as involving four important psychosocial aspect namely: emotional support (esteem, trust, affect, concern, listening), appraisal support (affirmation, feedback, social comparison), informational support (advice, suggestions, directives, information), and physical support (aid in-kind, money, labor, time and environmental modification). This support may increase employees’ predictability, purpose and hope while handling upsetting and threatening situations in the workplace (Mansor, Fontaine & Chong, 2003; Simpson, 2000).

Obviously, supervisor’s social support focuses on support for personal effectively at work and at the same time enables the employee’s ability to jointly manage work and family relationships. Within a job stress model, many scholars view that role ambiguity, role conflict and role overload, supervisor’s social support, and work intrusion on family conflict, but highly interrelated constructs. For example, the level of job stress will not interfere and create employees’ family conflicts when supervisors can adequately provide social support (e.g., emotional support, appraisal support and physical support) (Thomas & Ganster, 1995; Allen, Herst, Bruck & Sutton, 2000; Goldsen & Scharlach, 2001; Yu-Fei et al., 2012). Even though the nature of this relationship is interesting, the moderating role of supervisor’s social support is given less emphasized in the workplace stress research literature (Galinsky, Bond & Friedman, 1993; Fu & Shaffer, 2001; Yu-Fei et al., 2012). Many scholars argue that the role of supervisor’s social support as a moderating variable is given less attention in previous studies because they have used a segmented approach to separately describe the role of job stress features, supervisor’s social support characteristics, work intrusion on family conflict conditions, much employed a simple correlation method to assess the association of job stress and work intrusion on family conflict, and neglected to explain the influence of supervisor’s social support in increasing or decreasing the effect of job stress on employees’ family affairs. As a result, results from these studies have not provided sufficient useful information to be used as guidelines by practitioners in designing and managing employees’ physiological and psychological stresses in agile organizations (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Fu & Shaffer, 2001; Yu-Fei et al., 2012). Hence, it motivates the researchers to further explore the nature of this relationship.

2. Objective of the study

This study has three major objectives. Firstly, is to assess the relationship between role ambiguity, supervisor’s social support and work intrusion on family conflict. Secondly, is to assess the relationship between role conflict, supervisor’s social support and work intrusion on family conflict. Thirdly, is to assess the relationship between role overload, supervisor’s social support and work intrusion on family conflict.

3. Literature review

According to Burke and El-Kot (2010), Grandey, Cordeino and Crouter (2005) work-family conflict is considered to be an important issue in today’s business world. Nowadays, there has been an increasing interest in the conflict between work and family life domains, and recent studies highlight the conflict experienced by individuals between their roles in the family and at work, which is covered under the heading called work-family conflict. In Western countries work-family conflict researchers identified theories on the relationships between work demands and work-family conflict (Spector, Allen, Poelmans, Lapierre, Cooper & Widerszal-Bazyl, 2007). Other researchers also identified that long working hours, duty and heavy work load have a direct influence on work-family conflict (Boyar, Maertz, Mosley & Carr, 2008; Kim, Leong & Lee, 2005). So, it is important to establish a successful balance between work and family domains so that several demands in both domains could be met efficiently, and the required resources could be attained and used easily (Bass, Butler, Grzywacz & Linney, 2008).

Willis, O’Conner and Smith (2008) cited from the study of Greenhaus and Boutell defined work-family conflict as a consequence of inconsistent demands between the roles at work and in the family. In other words, work-family conflict exists when the expectations related to a certain role do not meet the requirements of the other role, preventing the efficient performance of that role (Greenhaus, Tammy & Spector, 2006). Therefore, it could be said that the conflict between work and family domains tends to stem from the conflict between the roles. Several studies reveal that work and family are not two separate domains as they are highly interdependent, having a dynamic relation with one another. While family life is affected by the factors at work, the reverse is also experienced (Trachtenberg, Anderson & Sabatelli, 2009; Namasivayam & Zhao, 2007).

Researchers identified the relationships between social support at work and employees health and wellbeing (Nabavi & Shahriari, 2012). Studied by McCall, Lombardo and Morrison (1988) found supervisor support facilitates employee job satisfaction, staff development; on-the-job learning and organizational commitment. According to Boyar and Mosley (2007) the support of the immediate supervisor has a central impact on the experience and perception of workplace well-being. In relation to work-family balance, researchers investigations into the role of social support at work have indicated a negative relationship between support and work-family conflict.

Several recent studies using an indirect effects model to measure the influence of social support in the relationship between job stress and work intrusion of family conflict using different samples, such as 800 employees from 29 academic departments and 34 administrative officers in Hong Kong University (Fu & Shaffer, 2001), 200 working women from teaching and healthcare professions in Nigeria (Hammed, 2008), and 96 employees in higher learning institutions in Sarawak (Yu-Fei et al., 2012). Findings from these studies reported that role ambiguity, role conflict and role overload problems had not increased employees’ family conflict when supervisors willing to provide adequate physical and moral support in the respective organizations (Fu & Shaffer, 2001; Hammed, 2008; Yu-Fei et al., 2012).

These studies are consistent with the notion of organizational behavior theory. For example, role theory (e.g., Kahn, Wolfe, Quinn, Snoek & Rosenthal, 1964; Katz & Kahn, 1978) suggests that differences between work and family roles, expectations and beliefs is an essential factor that may affect positive or negative conflict. Besides that, Edwards and Rothbard’s (2000) spillover theory explains that an individual’s first experience may subsequently affect his/her experience. For example, emotions and behavior (e.g., an employee’s mood) in one role will affect second role (e.g., interaction between an individual and his/her supervisor) and this may affect third factor (i.e., an employee who experiences bad or good interaction with his/her supervisor will bring this experience when he/she returns home). Application of this theory in a job stress model shows that the essence of supervisor’s social support is to promote positive relationship between work and family affairs. For example, the interference of work stress problems will not increase employees’ family conflict when supervisors keen to provide adequate material and moral support in the workplace (Fu & Shaffer, 2001; Hammed, 2008; Yu-Fei et al., 2012).

The literature has been used as a foundation to develop a conceptual framework for this study as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework

Based on the framework, it can be hypothesized that:

H1: Supervisor’s social support positively moderates the relationship between role ambiguityand work intrusion on family conflict.

H2: Supervisor’s social support positively moderates the relationship between role conflict and work intrusion on family conflict.

H3: Supervisor’s social support positively moderates the relationship between role overload and work intrusion on family conflict.

4. Methodology

This study used a cross-sectional method which allowed the researchers to integrate the job stress research literature, the semi-structured interview, the pilot study and the actual survey as a main procedure to collect data. The use of such methods may decrease the inadequacy of single method and increase the ability to gather accurate, less bias and high quality data (Cresswell, 1998; Ismail et al., 2010; Sekaran & Bougie, 2010). This study was conducted in a Malaysian government university in Borneo. The name of this organization is kept anonymous to avoid intrusiveness. In the first step of data collection, semi-structured interviews were conducted involving six experienced academic staff in the two types of faculty, namely science and technology based faculty and social science, humanities and liberal arts based faculty. They were selected using a purposive sampling technique because they have working experiences more than seven years and good knowledge about the nature of academic work practiced in their organizations. This interview method was used to understand the nature of job stress features, supervisor’s social support characteristics, and work intrusion on family conflict elements, as well as the relationship between such variables in the studied organization. The information gathered from such interviews was recorded, categorized according to the research variables, and constantly compared to the related literature in order to clearly understand the particular phenomena under study and put the research results in a proper context. Further, the results of the triangulation process were used as a guideline to develop the content of survey questionnaires for a pilot study. Next, a pilot study was done by discussing pilot questionnaires with the academic staff and information gathered from them was used to verify the content and format of survey questionnaire for an actual study. A back translation technique was used to translate the content of questionnaires in Malay and English languages in order to increase the validity and reliability of the instrument (Sekaran & Bougie, 2010; Wright, 1996).

4.1. Measurement

The independent variables for this study is job stress features, i.e., role ambiguity had 3 items, role conflict had 3 items, and role overload had 4 items that were developed based on job stress literature (Beehr & McGrath, 1992; Fu & Shaffer, 2001; Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985; Matteson & Invancevich, 1979). Moderating variables supervisor’s social support had 6 items that were developed based on supervisor support literature (Allen et al., 2000; Beehr & McGrath, 1992; Boles et al., 2001; Rhoades & Eisenberger, 2002; Turner, Frankel & Levin, 2004). The dependent variable for this study is work intrusion on family conflict had 6 items that were developed based on work intrusion on family conflict literature (Allen et al., 2000; Boles et al., 2001; Eby et al., 2005; Frone, Rusell & Cooper, 1992). These items were measured using a 7-item scale ranging from “very strongly disagree/dissatisfied” (1) to “very strongly agree/satisfied” (7). Demographic variables were used as controlling variables because this study focused on employee attitudes.

4.2. Study sample

The population for this study is 320 academic staffs who have worked in a Malaysian government university in Borneo. In the first step of data collection, the researchers met HR manager of the studied organization to get his permission to conduct this study and get his opinion about the rules for distributing survey questionnaires in his organization. Considering the organization rule, and length of study and financial constraints, 200 survey questionnaires were distributed to academic staff in 8 faculties of the organization using a convenient sampling technique. This sampling technique was chosen because the list of registered employees was not given to the researchers and this situation did not allow the researchers to choose randomly the respondents in the organizations. Of that total, 93 usable questionnaires were returned to the researchers, yielding 46.5 percent response rate. The survey questionnaires were answered by participants based on their consent and a voluntarily basis. The number of this sample exceeds the minimum sample of 30 participants as required by probability sampling technique, showing that it may be analyzed using inferential statistics (Cresswell, 1998; Sekaran & Bougie, 2010).

4.3. Data analysis technique

The SmartPLS 2.0 was employed to assess the validity and reliability of the instrument and thus test the research hypotheses (Henseler, Ringle & Sinkovics, 2009; Riggle, Edmondson & Hansen, 2009). The main advantage of using this method may deliver latent variable scores, avoid small sample size problems, estimate every complex models with many latent and manifest variables, hassle stringent assumptions about the distribution of variables and error terms, and handle both reflective and formative measurement models (Henseler et al., 2009; Riggle et al., 2009). A SmartPLS path model was employed to test the moderating effect of supervisor’s social support in the hypothesized model. This procedure stresses the development of a multiplicative term, which is used to encompass the interaction effect, and to calculate two R²s, one for the equation, which includes only main effects (main-effect model) and the other for a three-term equation (product-term model), which includes both the main and interaction effects. This technique may separate the component parts of the product term from the term itself to account for the complex combination of variance due to main and interaction effects (Henseler et al., 2009; Riggle et al., 2009). Results of an interaction are evident when the relationship between interacting terms and the dependent variable is significant (the value of t statistic ≥ 1.96). The fact that the significant main effects of predictor variables and moderator variables simultaneously exist in analysis it does not affect the moderator hypothesis and is significant to interpret the interaction term (Cohen & Cohen, 1983; Jaccard, Turrisi & Wan, 1990). Thus, a global fit measure is conducted to validate the adequacy of PLS path model globally based on Wetzels, Odekerken-Schroader & van Oppen's (2009) global fit measure. If the results of testing hypothesized model exceed the cut-off value of 0.36 for large effect sizes of R², showing that it adequately support the PLS path model globally (Wetzels et al., 2009).

5. Findings

Table 1 (see appendix) shows that most respondents were male (55.9 percent), with majority of the staff age between 40 years old to 45 years old (36.6 percent), with married staff making up around 79.6 percent and most of the respondents had served from 5 to 15 years (more than 80 percent).

|

Participant characteristics |

Sub-profile |

Percentage |

|

Gender |

Male Female |

55.9 44.1 |

|

Age |

< 27 28-33 34-39 40-45 > 45 |

24.7 5.4 24.7 36.6 8.6 |

|

Marital status |

Single Married |

20.4 79.6 |

|

Length of service |

1-5 years 6-10 years 11-15 years > 16 years |

46.2 18.3 22.6 12.9 |

Table 1. Participant characteristics (n = 93)

Table 2 shows the results of convergent and discriminant validity analyses. All constructs had the values of average variance extracted (AVE) larger than 0.5, indicating that they met the acceptable standard of convergent validity (Barclay, Higgins & Thompson, 1995; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Henseler et al., 2009). Besides that, all constructs had the values of √ AVE in diagonal were greater than the squared correlation with other constructs in off diagonal, showing that all constructs met the acceptable standard of discriminant validity (Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Henseler et al., 2009).

|

Variable |

AVE |

Role ambiguity |

Role conflict |

Role overload |

Supervisor’s social support |

Work-family conflict |

|

Role ambiguity |

0.865 |

0.930 |

|

|

|

|

|

Role conflict |

0.707 |

-0.035 |

0.841 |

|

|

|

|

Role overload |

0.704 |

-0.042 |

0.088 |

0.839 |

|

|

|

Supervisor’s social support |

0.718 |

0.323 |

0.284 |

0.546 |

0.847 |

|

|

Work intrusion on family conflict |

0.796 |

0.3383 |

0.344 |

0.234 |

0.413 |

0.892 |

Table 2. The results of convergent and discriminant validity analyses

Table 3 shows the factor loadings and cross loadings for different constructs. The correlation between items and factors had higher loadings than other items in the different constructs. The loadings of variables for their own constructs in the model were greater than 0.7, indicating that all constructs are considered adequate (Chin, 1998; Fornell & Larcker, 1981; Gefen & Straub, 2005; Henseler et al., 2009). In sum, the validity of measurement model met the criteria.

|

Construct/item |

Role ambiguity |

Role conflict |

Role overload |

Supervisor’s social support |

Work intrusion on family conflict |

|

Role ambiguity |

|||||

|

Clarity of job scope |

0.923399 |

-0.077449 |

-0.143925 |

0.125872 |

0.277636 |

|

Clarity of job description |

0.968817 |

-0.061246 |

-0.011624 |

0.390383 |

0.361154 |

|

Clarity of superior expectations |

0.896615 |

0.023555 |

0.046909 |

0.356989 |

0.295178 |

|

Role conflict |

|||||

|

In line with the organizational objectives. |

0.163723 |

0.886550 |

-0.008643 |

0.556575 |

0.237153 |

|

Execute extra tasks |

-0.144987 |

0.772103 |

0.227333 |

0.229329 |

0.061274 |

|

Follow my superior instructions |

-0.238554 |

0.854934 |

0.129773 |

0.440706 |

0.201362 |

|

Role overload |

|||||

|

Time for accomplish tasks |

0.017637 |

0.016462 |

0.909693 |

0.196735 |

0.387155 |

|

Excessive workloads. |

-0.064581 |

0.071015 |

0.851143 |

0.322277 |

0.226969 |

|

Execute multiple tasks |

-0.086367 |

0.205552 |

0.753719 |

0.242951 |

0.185424 |

|

Supervisor’s social support |

|||||

|

Understand about my family matters |

0.267462 |

0.351322 |

0.301485 |

0.842903 |

0.420940 |

|

Some time off from my family affairs |

0.256080 |

0.513954 |

0.252240 |

0.814555 |

0.155423 |

|

Looks out for my work-related problems. |

0.211283 |

0.492450 |

0.336665 |

0.880233 |

0.341602 |

|

Accommodate with my family/personal affairs |

0.447146 |

0.477826 |

0.206557 |

0.844924 |

0.388537 |

|

Understand about my personal/family issues. |

0.151357 |

0.544269 |

0.096761 |

0.852604 |

0.319549 |

|

Work intrusion on family conflict |

|||||

|

Affect my attitude at home |

0.185198 |

0.320981 |

0.404196 |

0.330143 |

0.915463 |

|

Enough time with my family |

0.318962 |

0.335431 |

0.277589 |

0.413007 |

0.890185 |

|

Enough time with my personal social activities |

0.300089 |

0.322121 |

0.389912 |

0.505261 |

0.921157 |

|

Concentration on my family |

0.299721 |

0.041294 |

0.293213 |

0.280054 |

0.886688 |

|

Affect relationship with my family. |

0.376465 |

0.057969 |

0.227157 |

0.393053 |

0.863231 |

|

Affect my concentrate towards my family |

0.349251 |

0.078172 |

0.208762 |

0.216388 |

0.874964 |

Table 3. The results of factor loadings and cross loadings for different constructs

Table 4 shows the results of reliability analysis for the instrument. The composite reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha had values of greater than 0.8, indicating that the instrument used in this study was high internal consistency (Henseler et al., 2009; Nunally & Benstein, 1994; Sekaran & Bougie, 2010).

|

Construct |

Composite reliability |

Cronbach Alpha |

|

Role ambiguity |

0.935594 |

0.920587 |

|

Role conflict |

0.873959 |

0.795345 |

|

Role overload |

0.885055 |

0.811917 |

|

Work-family conflict |

0.953284 |

0.936472 |

|

Reliability Estimation is Shown Diagonally |

||

Table 4. Composite reliability and Cronbach’s Alpha

The impact of multicollinearity is a concern for interpreting the regression variate (Hair, Anderson, Tatham & Black, 2006). Highly collinear variables can distort the results substantially and thus not generalizable. According to Bryman and Cramer (2001), the Pearson’s r between each pair of independent variables should not exceed 0.80, otherwise the independent variables that show a relationship at or in excess of 0.80 may be suspected of exhibiting multicollinearity. The output in Table 5 showed that none of the correlations between all independent variables exceed 0.80, which indicate that multicollinearity is not a problem in this study. These statistical results further confirm the validity and reliability of measurement scale used in this study.

|

Variable |

Pearson correlation analysis (r) |

||||

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

|

|

1. Role ambiguity |

1 |

|

|

|

|

|

2. Role conflict |

-.10 |

1 |

|

|

|

|

3. Role overload |

-.06 |

.17 |

1 |

|

|

|

4. Supervisor’s social support |

.29** |

.49** |

.29** |

1 |

. |

|

5. Work intrusion on family conflict |

.35** |

.15 |

.30** |

.36** |

1 |

|

Note: Significant at **p < 0.01 |

|||||

Table 5. Pearson correlation analysis and descriptive statistics

Figure 2 shows the outcomes of SmartPLS path model which explain that the interaction between role ambiguity and supervisor’s social support positively and significantly correlated with work intrusion on family conflict (Beta = 3.13; t = 2.35), therefore H1 was supported. In terms of explanatory power, the inclusion of these variables in the analysis had explained 30 percent of the variance in dependent variable. In sum, this result confirms that role ambiguity does act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role ambiguity and work intrusion on family conflict.

|

|

|

Note: Significant at t ≥ 1.96 |

Figure 2. The Results of SmartPLS Path Model Showing the Moderating Effect of Supervisor’s Social Support in Between Role Ambiguity and Work Intrusion on Family Conflict

In order to determine a global fit for the PLS path modeling, we carried out a global fit measure (GoF) based on Wetzels et al. (2009) guideline as follows: GoF=SQRT{MEAN (Communality of Endogenous) x MEAN (R²)}=0.493, indicating that it exceeds the cut-off value of 0.36 for large effect sizes of R². This result confirms that the PLS path model has better explaining power in comparison with the baseline values (GoF small=0.1, GoF medium=0.25, GoF large=0.36). It also provides adequate support to validate the PLS model globally (Wetzels et al., 2009).

Figure 3 shows the outcomes of SmartPLS path model which display that the interaction between role conflict and supervisor’s social support positively and insignificantly correlated with work intrusion on family conflict (Beta = 2.01; t = 1.33), therefore H2 was not supported. In terms of explanatory power, the inclusion of these variables in the analysis had explained 28 percent of the variance in dependent variable. In sum, this result confirms that role ambiguity does act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role conflict and work intrusion on family conflict.

|

|

|

Note: Significant at t ≥ 1.96 |

Figure 3. The Results of SmartPLS Path Model Showing the Moderating Effect of Supervisor’s Social Support in Between Role Conflict and Work Intrusion on Family Conflict

In order to determine a global fit for the PLS path modeling, we carried out a global fit measure (GoF) based on Wetzels et al. (2009) guideline as follows: GoF=SQRT{MEAN (Communality of Endogenous) x MEAN (R²)}=0.478, showing that it exceeds the cut-off value of 0.36 for large effect sizes of R². This result confirms that the PLS path model has better explaining power in comparison with the baseline values (GoF small=0.1, GoF medium=0.25, GoF large=0.36). It also provides adequate support to validate the PLS model globally (Wetzels et al., 2009).

Figure 4 shows the outcomes of SmartPLS path model which reveal that the interaction between role overload and supervisor’s social support positively and insignificantly correlated with work intrusion on family conflict (Beta = 3.13; t = 2.35), therefore H1 was supported. In terms of explanatory power, the inclusion of these variables in the analysis had explained 30 percent of the variance in dependent variable. In sum, this result confirms that role ambiguity does act as an important moderating variable in the relationship between role overload and work intrusion on family conflict.

|

|

|

Note: Significant at t ≥ 1.96 |

Figure 4. The Results of SmartPLS Path Model Showing the Moderating Effect of Supervisor’s Social Support in Between Role Overload and Work Intrusion on Family Conflict

In order to determine a global fit for the PLS path modeling, we carried out a global fit measure (GoF) based on Wetzels et al. (2009) guideline as follows: GoF = SQRT{MEAN (Communality of Endogenous) x MEAN (R²)}=0.459, signifying that it exceeds the cut-off value of 0.36 for large effect sizes of R². This result confirms that the PLS path model has better explaining power in comparison with the baseline values (GoF small = 0.1, GoF medium= 0.25, GoF large = 0.36). It also provides adequate support to validate the PLS model globally (Wetzels et al., 2009).

6. Discussion and implications

This study aims at examining the moderating effect of supervisor’s social support in the relationship between role ambiguity, role conflict as well as role overload and work intrusion on family conflict. The findings of this study highlight that interaction between role ambiguity and supervisor’s social support has decreased employees’ family conflict. In the context of this study, management teams have planned and implemented challenging jobs for academic staff in order to sustain and achieve their organizational strategies and goals. The interviewed respondents perceive that the levels of role ambiguity, role conflict and role overload are high, the willingness of supervisors to provide adequate social support are high, and the levels of work intrusion on family conflict are high. In this condition, the majority academic staff feel that the willingness of supervisors to properly provide social support have decreased the intrusion of role ambiguity problems in employees’ family affairs and increase their abilities to decrease family conflict.

The study presents three major implications: theoretical contribution, robustness of research methodology, and practical contribution. In terms of theoretical contribution, the results of this study reveal three important outcomes: firstly, supervisor’s social support has played an important role as a moderating variable in the relationship between role ambiguity and work intrusion on family conflict. This result is consistent with the studies by Fu and Shaffer (2001), Hammed (2008), and Yu-Fei et al. (2012). Secondly, supervisor’s social support has not played important roles as a moderating variable in the relationships of: a) between role conflict and work intrusion on family conflict, and b) between role overload and work intrusion on family conflict. These findings signify that having supervisory support per se is not enough in ameliorating work burden and work conflict with family issues in the background. Additionally, information gathered from the semi structured interviews reveals that this finding may be affected by external factors. Firstly, respondents who different backgrounds may have inconsistent views and judgments about the abilities of supervisors in solving role conflict and role overload among employees who have worked in different job categories. Secondly, individual employees have different capabilities and readiness to properly practice guidelines and methods as suggested by supervisors in overcoming their role conflict and role overload. These factors may overrule the effectiveness of supervisor’s social support in the job stress model of the workplace.

With respect to the robustness of research methodology, the survey questionnaires used in this study have exceeded the acceptable standards of the validity and reliability analyses may lead to produce accurate and reliable findings. In terms of practical contributions, the findings of this study can be used as guidelines by management to overcome job stress problems in organizations. The potential suggestions are: Firstly, update the content and methods of stress management training program. For example, the content of current training programs should focus on four domains: cognitive, affective, psychomotor and good moral values. The content of such trainings will be easily implemented if employees are trained using proper case studies and team building styles. Secondly, management needs to strengthen work groups and group cohesiveness. For example, involving employees in teamwork planning and administration will help them to increase positive socialization, improve career and psychosocial well-being. In a long term, it may lead to higher positive attitudinal and behavioral outcomes. Thirdly, improve work-life balance programs. For example, in order to reduce the employee physiological and psychological stresses, management should organize company trips for employees to relax their minds and bodies, as well as initiate physical fitness and sport games. Additionally, relaxation programs such as deep breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, massage therapy, yoga and mindfulness based activities and meditation might have positive additional values in reducing distress among employees. Fourthly, revisit the existing job designs based on the qualifications and expectations of individual employees may help to achieve the organizational key performance indicators.

Fifthly, revise compensation and benefits policies and procedures. For example, employer should allow paid stress leaves if proven by medical practitioners that an employee is suffering from stress-related disorder due to job stress. Additionally, swapping job roles might also help in alleviating the stress related symptoms experiencing by employees. Finally, an employer should introduce a systematic, on-going and organized services funded by employer such as Employee Assistance Programme (EAP) which helps the organization by providing counselling, advice, and help to employees and their families with problems arising from both work-related and external resources. If management pays attention to these suggestions this may increase the capability of employees to increase institutions of higher learning performance.

7. Conclusion

This study proposed a conceptual framework based on the workplace stress literature. The confirmatory factor analysis showed that the measurement scales met the acceptable standards of validity and reliability analyses. The outcomes of SmartPLS path model confirmed that supervisor’s social support did act an important moderating variable in the relationship between role ambiguity and work intrusion on family conflict. This finding also has supported and broadened the workplace stress research literature mostly published in Western countries. Conversely, supervisor’s social support did not act an important moderating variable in the relationships: a) between role conflict and work intrusion on family conflict, and b) between role overload and work intrusion on family conflict, Information gathered from the semi structured interview reveals that this result may be affected by two major external factors, namely different respondent perceptions about the abilities of supervisors in solving role conflict and role overload among employees who have worked in different job categories. Besides that, individual employees have different capabilities and readiness to properly practice guidelines and methods as suggested by supervisors in overcoming their role conflicts and role overloads. These factors may overrule the effectiveness of supervisor’s social support in the job stress model of the workplace. Therefore, current research and practice within the workplace stress needs to consider supervisor’s social support should be viewed as a crucial dimension of job stress domain. This study further suggests that the willingness of supervisors to adequately provide social support will strongly ability the capability of employees to cope with stress in implementing job. Consequently, it may induce positive subsequent attitudinal and behavioural outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, commitment, performance, ethics and balance life style). Thus, these positive outcomes may lead to maintain and support institutions of higher learning strategic missions in an era of global competition.

The conclusions drawn from this study should consider the following limitations. First, a cross-sectional research design used to gather data at one time within the period of study might not capture the causal connections between variables of interest. Second, this study does not specify the relationship between specific indicators for the independent variable, moderating variable and dependent variable. Third, the outcomes of SmartPLS path model have only focused on the level of performance variation explained by the regression equations, but there are still a number of unexplained factors that affect the causal relationship among variables and their relative explanatory power. Finally, the sample for this study was taken from one institution of higher learning that allowed the researchers to gather data via survey questionnaires. These limitations may decrease the ability to generalize the results of this study to other organizational settings.

The conceptual and methodological limitations of this study should be considered when designing future research. First, several organizational and personal characteristics should be further explored, as this may provide meaningful perspectives for understanding how individual similarities and differences affect the mentoring program within an organization. Second, other research designs (e.g., longitudinal studies) should be used to collect data and describe the patterns of change and the direction and magnitude of causal relationships between variables of interest. There has been an increased interest in the investigation on the impact of supervisor’s social support on long term psychological and organisational outcomes and this remains a significant area for future research. Third, to fully understand the effect of job stress on individual attitudes and behaviors via its impact upon supervisor’s social support, more organizations need to be used in future study. Fourth, other specific theoretical constructs of social support, such as coworker's social support, and manager's social support need to be considered because they have widely been recognized as an important link between supervisor’s role and many aspects of individual attitudes and behavior (Mohra & Wolfram,2010; Glazer, 2006). Fifth, response bias and common-method variance is a common issue in all questionnaire-based research. This research garnered the response rate of 46% which is acceptable but does show that views of only half the sample were reported. Therefore in inclusion of a larger sampling pool would also improve the generalizability of the reported results. Finally, other personal outcomes of job stress like satisfaction, commitment, performance, turnover and health should be considered given their prominence in job stress research literature (Karatepe & Kilic, 2007; Karatepe & Sokmen, 2006; Mohra & Wolframa,2010; Yildirim & Aycan, 2008). The importance of these issues needs to be further explained in future studies.

References

Allen, T.D., Herst, D.E.L., Bruck, C.S., & Sutton, M. (2000). Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: a review and agenda for the future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 5, 278-308. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1076-8998.5.2.278

Barclay, D., Higgins, C., & Thompson, R. (1995). The partial least squares (PLS) approach to causal modeling: Personal computer adoption and use as an illustration. Technology Study, 2 (2), 285-309.

Bass, L.B., Butler, B.A., Grzywacz, G.J., & Linney, D.K. (2008). Work-family conflict and job satisfaction: family resources as a buffer. Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 10(1), 24-30.

Beehr, T.A., & McGrath, J.E. (1992). Social support, occupational stress anxiety. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 5, 7-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10615809208250484

Bhatti, N., Shar, A., Shaikh, F., & Nazar, M. (2010). Causes of stress in organization, a case study of Sukkur. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(11), 3-14.

Bliese, P.D., & Britt, T.D. (2001). Role clarity, work overload, and organizational support: multi-level evidence of the importance of support. Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 22, 425-436. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/job.95

Boles, J., Howard, W.G., & Donofrio, H. (2001). An investigation into the inter-relationships of work-family conflict, family-work conflict, & work satisfaction. Journal of Managerial Issues, 13, 376-391.

Boyar, S.L. & Mosley, D.C. (2007). The relationship between core self-evaluations and work and family satisfaction: The mediating role of work–family conflict and facilitation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 71, 265-281. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.06.001

Boyar, S.L., Maertz, Jr.C.P., Mosley, Jr.C.D., & Carr, C.J. (2008). The impact of work/family demand on work-family conflict. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(3), 215-235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02683940810861356

Brouwers, A., Evers, W.J.G., & Welko, T. (2001). Self efficacy in eliciting social support and burnout among school teachers. Journal of applied Social Psychology, 31, 1474-1491. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2001.tb02683.x

Bryman, A., & Cramer, D. (2001). Quantitative Data Analysis with SPSS Release 10 for Windows: A Guide for Social Scientists. East Essex, Routledge.

Burke, R.J., & El-Kot, E.G. (2010). Correlates of work-family conflicts among managers in Egypt. International Journal of Islamic and Middle Eastern Finance and Management, 3(2), 113-131. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/17538391011054363

Chin, W.W. (1998). The partial least squares approach to structural equation modelling, in R.H. Hoyle (Eds.). Statistical Strategies for Small Sample Research (pp. 307-341). Thousand Oaks – California: Sage Publication, Inc.

Cohen, J., & Cohen, P. (1983). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioural sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Cresswell, J.W. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. London: SAGE Publications.

Dar, L., Akmal. A, Naseem, M.A., & Khan, K.U.D. (2011). Impact of Stress on Employees Job Performance in Business Sector of Pakistan. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 11 (6), 1-5.

Eby, L.T., Casper, W.J., Lockwood, A., Bordeaux, C., & Brinley, A. (2005). Work and family research in IO/OB: Content analysis and review of the literature (1980-2002). Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66, 124-197. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.11.003

Edwards, J.R., & Rothbard, N.P. (2000). Mechanisms linking work and family: clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Academy of Management Review, 25, 178‑199.

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D.F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, XVIII, 39-50. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/3151312

Frone, M.R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M.L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65‑78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.77.1.65

Fu, C.K., & Shaffer, M.A. (2001). The tug of work and family: direct and indirect domain-specific determinants of work-family conflict. Personnel Review, 30, 502-522. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000005936

Galinsky, E., Bond, J., & Friedman, D. (1993). The changing workforce: Highlights of the National study. New York: Families and Work Institute.

Gefen, D. & Straub, D. (2005). A practical guide to factorial validity using PLS-Graph: Tutorial and annotated example. Communication of the Association for Information Systems, 16, 91‑109.

Glazer, S. (2006). Social support across cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30 (5), 605-622. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2005.01.013

Goldsen, K.I., & Scharlach, A.E. (2001). Families and work: New directions in the twenty-first century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Grandey, A.A., Cordeino, L.B., & Crouter, C.A. (2005). A longitudinal and multi-source test of the work-family conflict and job satisfaction relationship. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 78, 305-323. http://dx.doi.org/10.1348/096317905X26769

Greenhaus, H.J., Tammy, D.A., & Spector, P.E. (2006). Health consequences of work-family: the dark side of the work-family interface. Research in Occopational Stress and Well-Being, 5, 61-98.

Greenhaus, J.H. & Beutell, N.J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10, 76-88.

Hair, J.F., Anderson, R.E., Tatham, R.L., & Black, W.C. (2006). Multivariate data analysis. New Jersey: Prentice Hall International, Inc.

Hammed, A. (2008). The interactive effect of stress, social support and work-family conflict on Nigerian women's mental health. European Journal of Social Sciences 7(2), 53-65.

Henseler, J., Ringle, C., & Sinkovics, R. (2009). The use of Pertial Least Square Path modeling in international Marketing. Advances in International Marketing, 20, 277-319. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/S1474-7979(2009)0000020014

House, J.S. (2003). Job stress and social support. Reading Mass: Addison-Wesley.

Ismail, A., Mohamed, H.A.B., Sulaiman, A.Z., Ismail, Z., & Mahmood, W.N.W. (2010). Relationship between work stress, coworker’s social support, work stress and work interference with family conflict: An empirical study in Malaysia. International Business Management, 4(2), 76-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.3923/ibm.2010.76.83

Jaccard, J., Turrisi, R., & Wan, C.K. (1990). Interaction effects in multiple regression. Newsbury Park, California: SAGE Publications, Inc.

Kahn, R.L., Wolfe, D.M., Quinn, R.P., Snoek, J.D., & Rosenthal, R.A. (1964). Organizational stress: studies in role conflict and ambiguity. New York: Wiley.

Karasek, R.A. (1985). Job content questionnaire and user's guide. Lowell: University of Massachusetts Lowell.

Karatepe O.M., & Sokmen, A. (2006). The effects of work role and family role variables on psychologic al and behavioral outcomes of frontline employees. Tourism Management, 27(2), 255-268. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.10.001

Karatepe, O.M., & Kilic, H. (2007). The Corresponding Author Relationships of supervisor support and conflicts in the work–family interface with the selected job outcomes of frontline employees. Tourism Management, 28 (1), 238-252. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.12.019

Katz, D., & Kahn, R. (1978). The social psychology of organizations. New York: Wiley.

Kim, W.G., Leong, J.K., & Lee, Y.K. (2005). Effect of service orientation on job satisfaction, organizational commitment, and intention of leaving in a casual dining chain restaurant. Hospitality Management, 24, 171-193. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2004.05.004

Lazarus, R.S., (1966). Psychological Stress and the Coping Process. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Major, V.S., Klein, K.J. & Ehrhart, M.G. (2002). Work time, work interference with family, and psychological distress. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87, 427-436. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.3.427

Mansor, A.T., Fontaine, R., & Chong, S.C. (2003). Occupational stress among managers: a Malaysian survey. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 18(6), 622-628. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02683940310494412

Matteson, M.T., & Ivancevich, J.M. (1979). Organizational stressors and heart disease: A research model. Academy of Management Review, 4, 347-357.

McCall, M., Lombardo, M., & Morrison, A. (1988). Lessons of experience: How successful executives develop on the job. Free Press.

Mohra, G., & Wolfram, H.J. (2010). Stress Among Managers: The Importance of Dynamic Tasks, Predictability, and Social Support in Unpredictable Times. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15 (2), 167-179. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018892

Nabavi, A.H., & Shahryari, M. (2012). Linkage Between Worksite Support with Work Role Expectation, Role Ambiguity and Its Effects on Work-Family Conflict, Canadian Social Science, 8(4), 112-119.

Namasivayam, K., & Zhao, X. (2007). An investigation of the moderating effects of organizational commitment on the relationships between work-family conflict and job satisfaction among hospitality employees in India. Tourism Management, 28, 1212-1223. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.09.021

Nunally, J.C., & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychometric Theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

O’Driscoll, M., & Brough, P. (2003). Job stress and burnout. In O’Driscoll, M., Taylor, P., & Kalliath, T. (Eds.). Organizational Psychology in Australia and New Zealand, 188-211. Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Poelmans, S. (2001). A multi-level, multi-method study of work-family conflict: A managerial perspective. Spain: Universidad de Navarra.

Rhoades, L., & Eisenberger, R. (2002). Perceived organizational support: A review of the literature. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(4), 698-714. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.87.4.698

Riggle, R., Edmondson, D., & Hansen, J. (2009). A Meta-analysis of the Relationship Between Perceived Organizational Support and Job Outcomes: 20 Years of Research. Journal of Business Research, 62(10), 1027-1030. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.05.003

Schiem, S., & Young, M. (2010). The demands of creative work: Implications for stress in the work–family interface. Social Science Research, 39(2), 246-259. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.05.008

Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2010). Research methods for business: A skill building approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Simpson, M.E. (2000). Societal support and education. Handbook on stress and anxiety: Contemporary knowledge, theory and treatment. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Spector, P.E., Allen, T.D., Poelmans, S.A.Y., Lapierre, M.L., Cooper, C.L., & Widerszal-Bazyl, M. (2007). Cross-national differences in relationships of work demands, job satisfaction, and turnover intentions with work-family conflict. Personnel Psychology, 60, 805-835. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00092.x

Thomas, L.T., & Ganster, D.C. (1995). Impact of family-supportive work variables on work-family conflict and strain: a control perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80, 6-15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.80.1.6

Trachtenberg, V.J., Anderson, A.S., & Sabatelli, M.R. (2009). Work-home conflict and domestic violence: A test of a conceptual Model. Journal of Family Violence, 24, 471-483. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9246-3

Turner, R.J., Frankel, B.G., & Levin, D. (2004). Social support: Conceptualization, measurement, and implications for mental health. Ontario: Health Career Research Unit, University of Western Ontario.

Viswesvaran, C., Sanchez, J.I., & Fisher, J. (1999). The role of social support in the process of work stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(2), 314-334. http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1661

Wetzels, M., Odekerken-Schröder, G., & van Oppen, C. (2009). Using PLS path modeling for assessing hierarchical construct models: guidelines and empirical illustration. MIS Quarterly, 33(1), 177- 195.

Willis, A.T., O’Conner, B.D., & Smith, L. (2008). Investigating effort-reward imbalance and work-family conflict in relation to morningness-eveningness and shift work. Work & Stres, 22(2), 125-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02678370802180558

Wright, L.L. (1996). Qualitative international management research. In Punnett, B.J., & Shenkar, O. (Eds.). Handbook for International Management Research, 63-81. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Yildirim, D., & Aycan, Z. (2008). Nurses’ work demands and work–family conflict: A questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(9), 1366-1378. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.10.010

Yu-Fei, M.C., Ismail, A., Ahmad, R., & Kuek, T.Y. (2012). Impacts of job stress characteristics on the workforce – organizational social support as the moderator. South-Asia Journal of Marketing and Management Research, 2(3), 1-20.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

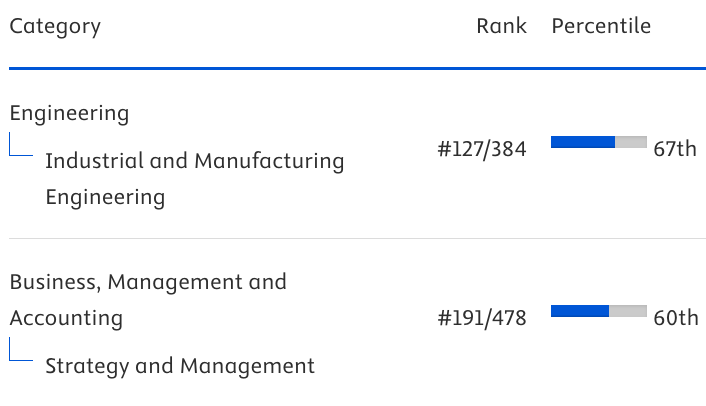

Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management, 2008-2026

Online ISSN: 2013-0953; Print ISSN: 2013-8423; Online DL: B-28744-2008

Publisher: OmniaScience